By 700BC Athens evolved from a monarchy to an aristocracy. Although the land owning nobles were pleased with their newly found power, envy and vexation swept the nation. Fed up with their prolonged suffering, the ordinary, poverty-stricken citizens demanded change in their government. As civil unrest stirred, a seed of democratic salvation was planted. Over time, the roots of democracy bore deeper into the soil and the idealistic idea spread. Finally, after methodical cultivation from several leaders, the seed blossomed into first-rate democracy for all of Athens. With sovereign structure that ran like clockwork, a couple of altruistic leaders and dynamic events, and superiority over arguably all other societies, Athens did the most to encourage democratic government.

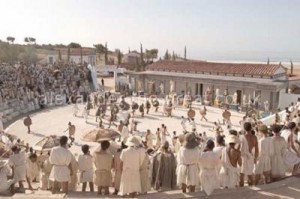

The groundbreaking structure of Athenian democracy put the past ways of monopolizing aristocrats to shame. However, Athens was not exactly a utopian society with vast equality. During the fourth century, there were about two hundred and sixty thousand people living in Athens, but only about forty thousand could participate in the democratic process. The other two-hundred and twenty thousand adolescents, women, foreigners, and slaves were “filtered out,” hence the “limited” in “limited democracy.” Citizenship in Athens was far from all-inclusive. You could only be a citizen with rights if you were a male that was older than 18 and had both parent citizens. Moreover, Athenian democracy consisted of three imperative institutions: the Ekklasia, Boule, and Dikasteria. The Ekklasia, commonly referred to as the Assembly, was the sovereign backbone for all of Athens. The Ekklasia met forty times per year and any one of the forty thousand male citizens over eighteen was sanctioned to participate. The meeting covered a variety of topics such as: war, foreign policy, new laws, and the behavior of public officials. In addition, the Ekklasia would also hold a special meeting once a year, to vote to ostracize or exile an individual. The Ekklasia came to an agreement by the simple, but effective majority-rules voting method.

The Boule, or Council of Five-Hundred, was the second foundation of Athenian democracy. The Boule, comprised of Five-Hundred men, fifty from each independent tribe, chosen at random, met daily and took care of the more participatory governmental needs like overseeing the workers, battle ships, army horses, and meetings with other ambassadors from various city states. They also decided what issues would and would not be concerned with the Ekklasia.

The third and final important institution was the Dikasteria, also known as the jury. The jury was mad up of five hundred male citizens over thirty, who were chosen randomly, covered the more legal side of democratic government. Since there were no police in Ancient Greece, the jury brought justice and peace, by convicting those who let their better judgment cease. In other words, they would prevent corruption by hearing out the prosecutor’s conviction and the accused person’s side of things, and then determining, based on what the heard, whether the defendant was guilty or innocent. The first written law in Ancient Greece dates all the way back to 620BC, and says that anybody who commits murder is subject to exile. Draco and Solon were the primary law writers in Ancient Greece. Following the homicide and exile law, a series of many more written laws began to flow in, providing Athens with legislative bearings to assist in the legal part of democracy later on. The methodical, just, and efficient structure of Athenian democracy was quite progressive for the time period.

Several significantly influential leaders and events also contributed to the righteousness of Athenian democracy. Cleisthenes, the first altruistic tyrant to take a step in the direction of democracy, furthered the involvement of ordinary citizens in government by implementing the Boule, who, again, was chosen randomly to ensure fairness. Although for his time he was extremely revolutionary, Cleisthenes was just the water, and for the seed of salvation to blossom, you need sun, bees, and other things. The sun took on the form of The Persian Wars, a series of conflicts between the Archamenied Empire of Persia and the Greek city-states of the Hellenic world that lasted for about 20 years, which slingshot Athens into a state of ecstasy, independence, and authority. After their heroic victory over the mighty Persian army, the Greeks formed what is known as the Delian League, a sort of alliance directed by Athens. The Delian League provided Athens with an unquestionable position of authority over the other city-states. This helped increase the magnitude and viability of Athenian democracy because it allowed Athens to, in a way, forcefully implement and instigate democracy. Call him whatever you want, the bees, the fertilizer, even the artificial crop producing potion, Pericles, a visionary who came into power around 461BC, was the final major factor for democratic blossoming. Under Pericles’ skilled leadership Athenian democracy flourished. His single major reform required the city to pay a base salary, or stipend, to its government officials. This reform allowed for more participation from the common class of citizens, who previously had a very hard time voicing their opinions. Between Cleisthenes, The Persian Wars, and Pericles, Athenian democracy was able to blossom into something glorious.

Due to the revolutionary thinking of the Athenians, Athens contributed numerous reforms and fundamental principals to the human ideal of democracy. Other than the exclusive part of Athenian government, some of the most progressive democracies today adopted and modified almost all of the Ancient democracy invented by Athens. Take the jury for example. The United States, arguably the most progressive modern democracy, uses a similar jury system to the one Athens invented many centuries ago. Although there are some modifications such as jury size and a unanimous voting style, the basic principal of the jury remains intact. The timeless ingenuity of Athens was not only progressive in the fourth century, but twenty-first century as well.

Sovereign structure, a handful of influential people and events, topped off with a revolutionary and timeless way of thinking: an Ancient Athenian recipe for successful and thriving democracy. The three imperative institutions that held democracy together put the oppressive autocratic system before it to shame. Cleisthenes, The Persian Wars, and Pericles, helped democracy to eventually blossom. And finally, the revolutionary way of thinking held strong throughout the centuries and remains radical today. Although Athenian democracy started out a diminutive seed, after careful cultivation, it has blossomed into a strong, everlasting tree.

Latest posts by Wescott (see all)

- Bottle Opener Collection - September 4, 2014

- Shoes - July 21, 2014

- The Airplane Window - July 16, 2014

One Comment